(June 2013)

INTRODUCTION

Commercial and personal

lines insurance coverage forms and policies both cover windstorm and hail

damage. As with fire and explosion, they do not define these terms. As a

result, dictionary definitions and court precedents must be used to determine

losses that are covered and those that are not. The Insurance Services Office

(ISO) CP 10 10–Causes of Loss–Basic Form and CP 10 20–Causes of Loss–Broad Form

cover windstorm and hail but exclude loss or damage caused by or that results

from:

- Frost

- Cold weather

- Ice, snow, or sleet

Note: This does not include hail.

- Interior damage to buildings or structures (or

personal property located inside a building or structure caused by rain,

snow, sand, or dust) unless these damaging elements entered the interior

through breaches or openings made in the roof or walls

The last two exclusions

specifically state that the exclusion applies regardless of whether the element

was wind-driven or not.

CP 10 30–Causes of

Loss–Special Form approaches things a bit differently. It does not specifically

list windstorm or hail as covered but coverage applies because neither is

excluded. However, it excludes loss or damage caused by rain, snow, ice, or

sleet, or damage to personal property in the open. It also limits damage to the

interior of the building or structure and to personal property inside from

rain, sleet, sand, or dust to apply only if a covered cause of loss first

breaches or damages the building and that allows the elements to enter. The

limitation states that coverage does not apply unless the building or structure

is first breached or damaged, even if the elements are wind-driven.

Related Court Cases:

"Opening" In Roof as Condition of Interior Damage Coverage Examined

Storm Damage

Held Not Covered By Virtue Of Ice, Snow, or Sleet Exclusion

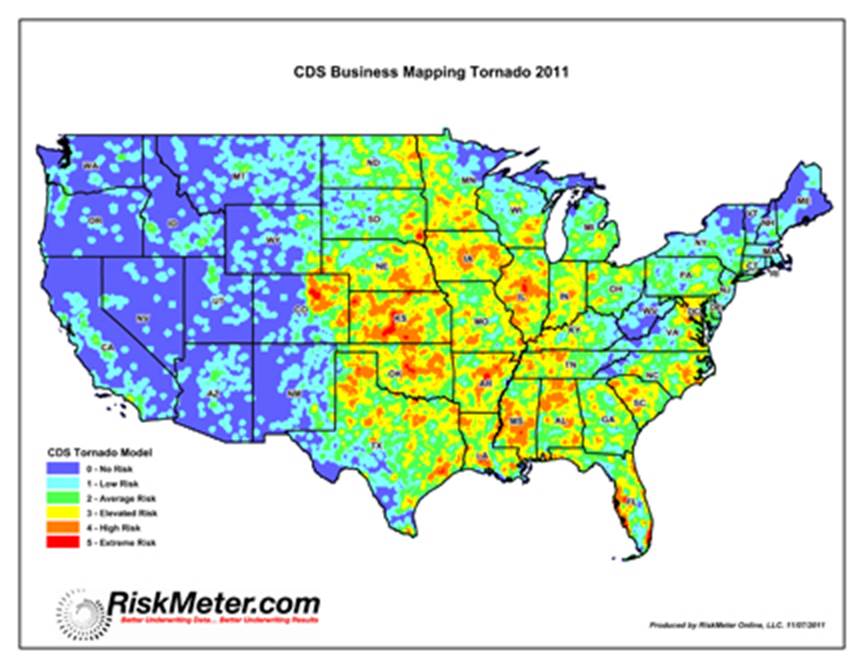

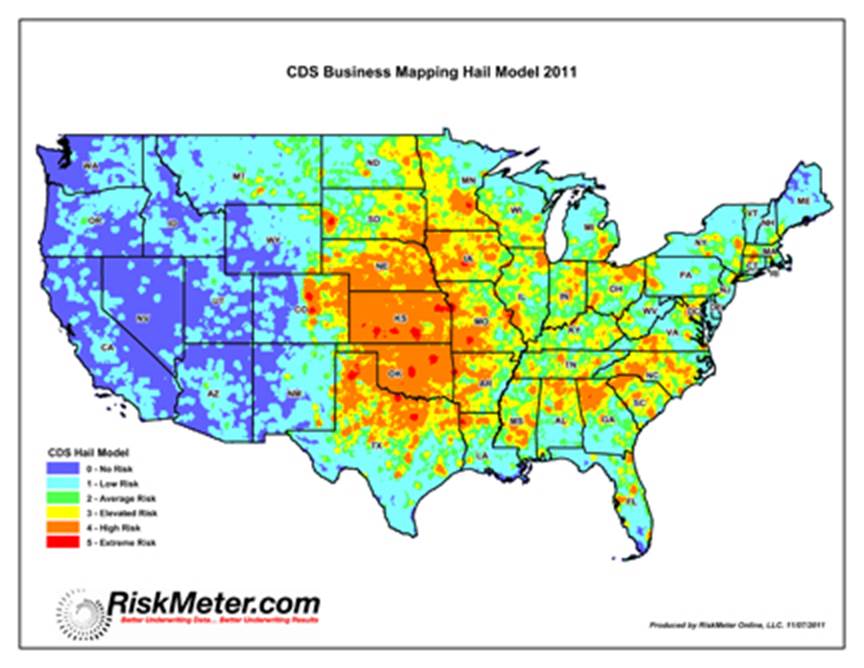

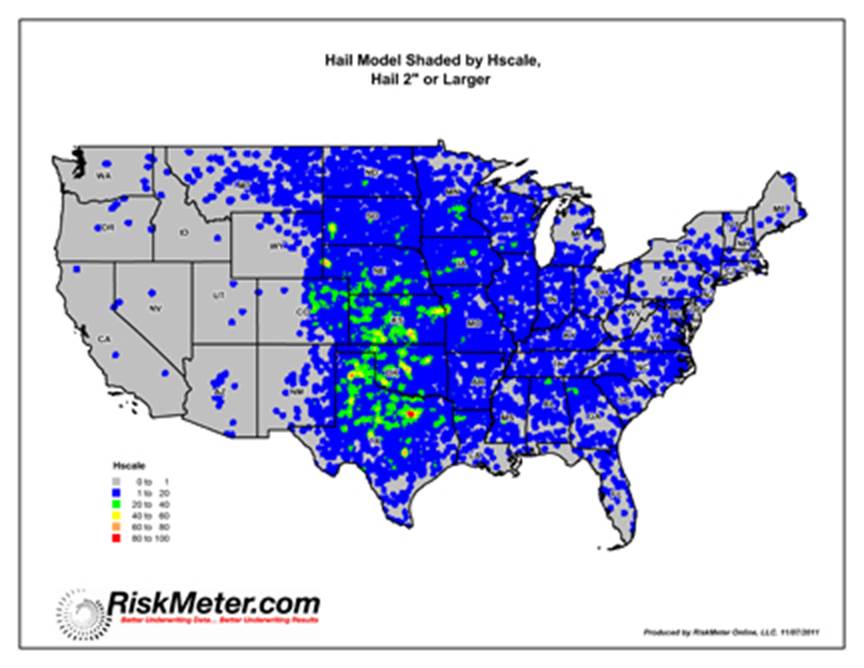

Note: All maps

used in this article are copyrighted by and used with the permission of CDS

Business Mapping at www.cdsys.com.

DEFINITIONS

Several terms must be

defined to better understand the coverages provided. Each is the dictionary

definition or as defined in scientific or research articles and papers. Black's

Law Dictionary does not define any of these terms.

The American

Heritage Science Dictionary

defines rain as water

that condenses from water vapor in the atmosphere that falls to Earth as

separate drops from clouds.

The American

Heritage College Dictionary defines wind as moving air, especially a

natural and perceptible movement of air parallel to or along the ground.

The American Heritage Science Dictionary

defines wind as a current of air,

especially a natural one, that moves along or parallel to the ground, moving

from an area of high pressure to an area of low pressure.

The American

Heritage College Dictionary

defines windstorm as a storm with high winds or violent gusts but with

little or no rain.

· Hail

The America

Heritage College Dictionary

defines hail as precipitation in the form of spherical or irregular

pellets of ice larger than 5 millimeters (0.2 inches) in diameter.

WINDSTORM

Wind and windstorm are

different causes of loss. Consider the following loss examples:

- The light breeze that blows through the house from

the front to the back often causes the front door to slam. This results in

cracked window frames and panes.

- A storm door left ajar slams constantly against the

outside wall of the house. This causes a crack to develop in the outside

wall.

- A strong blast of wind enters the home through a mesh

screen door and blows over a lamp.

Wind causes these losses.

Insurance coverage does not apply because the loss or damage is not a direct

result of windstorm.

Windstorm refers only to

the wind. It does not refer to the rain and water that may accompany it. This

very important distinction is frequently made following a hurricane. Hurricanes

and tornados are not defined in any insurance coverage, even though both terms

contribute to the lively discussion of what is covered. Windstorm damage is

limited to damage the wind causes. Water damage that may accompany the

windstorm is not covered as windstorm. In addition, sand driven by wind is also

excluded.

|

Examples:

- Siding ripped from the side of a house is covered

because the wind caused the siding to rip.

- Sand driven by the wind through gaps in the

windows, doors, and siding is not covered because the wind did not

damage the structure. The sand did the damage.

- A wind-driven wave surge floods a building. This is

the major point of dispute following a hurricane. What damage did the

wind cause and what damage did the flood cause?

|

In August 2011 RiskMeter Online announced that the following are the top

ten tornado-prone areas in the United States, based on its research:

- Denver,

CO (rural, not urban)

- Hialeah,

FL

- Miami, FL

- Hollywood,

FL

- Aurora,

CO

- Houston,

TX

- Commerce

City, CO

- Tampa, FL

- St.

Petersburg, FL

- North

Little Rock, AR

HAIL

Hail falls along paths

scientists call hail swaths. Their size can vary from a few acres to up to 10

miles wide, 100 miles long, and leave piles of hail that must be removed by

snowplows or bulldozers. Hail causes significant damage to crops in the United

States every year, in amounts that run into the hundreds of millions of

dollars. Farmers cope with the hail hazard by purchasing insurance.

Hail in the United States

is most prevalent in the area known as "Hail Alley." This consists of

the states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. Parts of this region

average between seven and nine hail days per year. Hail is also much more

common along mountain ranges because mountains force horizontal winds upwards.

This intensifies the updrafts within thunderstorms and makes hail more likely.

In September 2011 RiskMeter Online announced that the following are the top

ten hail prone areas in the United States, based on its research:

- Amarillo,

TX

- Wichita,

KS

- Tulsa, OK

- Oklahoma

City, OK

- Midwest

City, OK

- Aurora,

CO

- Colorado

Springs, CO

- Kansas

City, KS

- Fort

Worth, TX

- Denver,

CO

WINDSTORM EXCLUSIONS AND DEDUCTIBLES

Many insurance companies

issue policies that exclude windstorm (or make the coverage subject to

significant deductibles) because of concern about potential hurricane damage.

Properties subject to

windstorm exclusions may be eligible for coverage in a Beach FAIR Plan. These

plans are available in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North

Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas. They cover virtually all real and personal

property in the designated beach area. There are variations in the type of

eligible property among the various states. Each state has a maximum limit per

structure but the limits change regularly. It is important to investigate the

plans in each state to determine the cap. These plans are NOT a substitute for

the coverage the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) provides. Beach FAIR

Plan policies cover only wind damage. NFIP flood policies cover only flood

damage.

Related Article:

Overview of the National Flood Insurance Program

When a separate windstorm

deductible is used, it is usually a percentage deductible based on the limit of

insurance, not the value of the loss. Most windstorm deductible endorsements

are state-specific and should be read carefully and explained to the insured

thoroughly because of the way they are applied.

|

Example: Michelle owns a large apartment building and insures if

for $3,000,000. She has a $1,000 deductible on all causes of loss except

windstorm, which is subject to a 5% deductible. A windstorm causes $50,000 in

damage to her building. She expects to receive $50,000 - $2,500 ($50,000 X

.05) or $47,500 for her claim. She is very surprised and extremely

disappointed when informed that her deductible is actually $150,000

($3,000,000 X .05) and that she will not receive anything for her $50,000

loss.

|

Note: These same

exclusions and deductible forms can be used in areas of the Midwest where hail

may be a major concern.

CONCLUSION

When does wind become a

windstorm? Was there really hail damage or was it an existing condition? The

observation of damage is the only determining factor and damage unfortunately

is in the “eye of the beholder.” The claims adjustor and the insured may have

differences of opinion that only an impartial court of law can resolve. Because

scientific evidence is important to any argument, the following three different

wind scales are presented that may be cited to justify either side of the

argument.

BEAUFORT WIND SCALE

British Rear-Admiral Sir

Francis Beaufort developed this scale in 1805, based on his observations of the

effects of wind. He was a British hydrographer (a

scientist who studies surface waters, especially with regard to navigating

them). This is the earliest formal wind scale. It provides the standards of

wind velocity measurements that mariners and the United States Weather Bureau

use, with some modifications made for terminology. These meteorological

standards are helpful to clarify the meaning of "windstorm" for

insurance purposes. This wind scale differs from the others in that it measures

straight-line wind forces as opposed to the effects of rotating winds.

The speed of a current of

air and its direction determines whether it is harmful or beneficial. A wind

current of 19 to 24 miles an hour is classified as a fresh breeze and is not

harmful. When wind reaches a speed of 48 miles an hour, it is classified as a

strong gale and may cause some damage to fruit crops. At 64 to 75 miles per

hour, wind is classified as a windstorm and is dangerous to both crops and

property. Hurricanes and tornadoes involve winds in excess of 75 miles per

hour. The Beaufort Wind Scale, based on the effect of wind on ships, and

adopted in substance by the United States Weather Bureau, appears below.

Beaufort Wind Scale

|

|

Scale

|

Wind Description Wave Height in feet

|

Speed

(mph)

|

Speed

(knots)

|

Effects on land or sea

|

|

0

|

Calm

None

|

0–1

|

0–1

|

Smoke rises vertically.

Sea is like a mirror.

|

|

1

|

Light air

0.25

|

1–3

|

1–3

|

Smoke drifts slowly.

Ripples on the water appear as scales.

|

|

2

|

Light breeze

0.5–1.0

|

4–7

|

4–6

|

Leaves rustle. Small

wavelets. Crests appear glassy.

|

|

3

|

Gentle breeze

2.0–3.0

|

8–12

|

7–10

|

Leaves and twigs move.

Large wavelets. Crests break. Scattered whitecaps.

|

|

4

|

Moderate breeze

3.5–5.0

|

13–18

|

11–16

|

Small branches move.

Small waves become longer. Numerous whitecaps.

|

|

5

|

Fresh breeze

6.0–8.0

|

19–24

|

17–21

|

Small trees sway.

Moderate waves. Many whitecaps. Spray

|

|

6

|

Strong breeze

9.5–13.0

|

25–31

|

22–27

|

Large branches sway.

Larger waves. Whitecaps. Spray.

|

|

7

|

Moderate (near) gale

13.5–19.0

|

32–38

|

28–33

|

Whole trees move. Sea

heaps up. White foam from waves.

|

|

8

|

Gale

18.0–25.0

|

39–46

|

34–40

|

Twigs break off trees.

Medium high and long waves.

|

|

9

|

Strong gale

23.0–32.0

|

47–54

|

41–47

|

Branches break. High

waves. Sea rolls. Foam. Low visibility.

|

|

10

|

Whole gale/storm

29.0–41.0

|

55–63

|

48–55

|

Trees snap and blow

down. High waves and overhanging crests. Heavy rolling.

|

|

11

|

Violent storm

37.0–52.0

|

64–75

|

56–63

|

Widespread damage.

Exceptionally high waves.

|

|

12

|

Hurricane

45.0 and over

|

Over 75

|

Over 64

|

Extreme damage. Air

filled with foam. Sea completely white with driving spray.

|

ENHANCED FUJITA SCALE (EF SCALE)

This scale was introduced

to the public in 2007. The previous scale was introduced in 1971 before there

were many more advanced meteorological measuring devices. This new table still

depends on observations at the scene of the tornado’s impact but more

accurately estimates a tornado's speed. Tornadoes may develop a counterclockwise,

swirling motion that exceeds 100 miles per hour and cause incredible

destruction. Tornadoes occur most often in the central Mississippi Valley

region of the United States. It is important to note that neither the size of

the funnel nor the length of time it remains on the ground have any effect on

the scale.

Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF Scale)

|

|

Scale

|

Description

|

Speed

|

Effects

|

|

|

Light damage

|

65-85 mph

|

Some roof, gutter and

siding damage. Limited amount of branches broken from trees and some shallow

rooted trees pushed over.

|

|

EF1

|

Moderate damage

|

86-110 mph

|

Severe roof damage. Overturned

and badly damaged mobile homes. Exterior doors and windows lost and glass

broken.

|

|

EF2

|

Considerable damage

|

111–135 mph

|

Roofs torn off. Home

foundations shift. Complete destruction of mobile homes. Uprooting or

breaking of large trees. Small or light objects turned into missiles. Winds

lift cars off the ground.

|

|

EF3

|

Severe damage

|

136–165 mph

|

Destruction of upper

levels of well-constructed homes. Large buildings such as shopping malls

severely damaged. Debarking of trees. Overturning of trains. Wind lifts and

throws heavy cars. Any structure without a substantial foundation blown a

distance away.

|

|

EF4

|

Devastating damage

|

|

Leveling of

well-constructed houses. Cars thrown and small missiles generated.

|

|

EF5

|

Incredible damage

|

Over 200 mph

|

Well-constructed houses

pulled off foundations and swept away. Heavy items such as automobiles become

missiles. Significant damage to steel reinforced concrete structures. Structural

damage to high-rise buildings.

|

SAFFIR-SIMPSON WIND SCALE

The Saffir-Simpson

wind scale places a hurricane in one of five categories according to its

strength. It was created in the early 1970s. Category one is the weakest

hurricane strength measured and category five is the strongest. A hurricane's

strength is based on its wind speed. The height of the storm surge depends on

the slope of the continental shelf connected to the area where the storm

strikes. Wind speeds below 74 miles per hour are measured according to the

Beaufort Wind Scale. This scale rates the severity of a hurricane based on its

barometric pressure, wind speed, storm surge, and damage potential.

Saffir-Simpson Wind Scale

|

|

Scale

|

Barometric Pressure

|

Wind Speed

|

Storm Surge

|

Damage

|

Effects

|

|

1

|

Greater than 28.94

|

74–95 mph

|

4–5 feet

|

Minimal–Gale force

|

No real damage to

building structures. Damage primarily to unanchored mobile homes, shrubbery,

and trees. Some coastal flooding of low-lying roads and minor pier damage.

Storm surge 4 to 5 feet above normal.

Examples: Hurricane Lili in 2002 and

Hurricane Gaston in 2004

|

|

2

|

28.50 to 28.93

|

96–110 mph

|

|

Moderate force

|

Some roofing material,

door, and window damage to buildings. Considerable damage to shrubbery, trees,

and mobile homes. Flooding damages piers. Small craft in unprotected moorings

may break their moorings. Storm surge 6 to 8 feet above normal.

Example: Hurricane Isabel in 2003 and Hurricane Frances in 2004

|

|

3

|

27.91 to 28.49

|

111–130 mph

|

9–12 feet

|

Extensive–Significant

force

|

Some structural damage

to small residences and utility buildings. Large trees blown down. Mobile

homes destroyed. Coastal flooding destroys smaller structures. Larger coastal

structures damaged by floating debris. Terrain lower than 5 feet at sea level

flooded 8 miles or more inland. Evacuation of low-lying residences near the

coastline. Storm surge 9 to 12 feet above normal.

Example: Hurricanes Jeanne and Ivan in 2004. Hurricane Katrina in 2005

was a category 4 in the Gulf of Mexico but was only a category 3 when it made

landfall.

|

|

4

|

27.17 to 27.90

|

131–155 mph

|

13–18 feet

|

Extreme force

|

Severe damage to roofs,

doors, and windows. Mobile homes completely destroyed. Major beach erosion.

Major damage to lower floors of shoreline structures. Low-lying areas flooded

up to 6 miles inland. Massive evacuation of residential areas up to 6 miles

inland. Storm surge 13 to 18 feet above normal.

Examples: Hurricane Charlie in 2004 and Hurricane Dennis in 2005

|

|

5

|

Less than 27.17

|

|

Over 18 feet

|

Catas-

trophic

|

Complete roof failure

on many residences and industrial buildings. Some complete building failures.

Small utility buildings overturned or blown away. Major flooding damage to

lower floors of structures located less than 15 feet above sea level and

within 500 yards of the shoreline. Massive evacuation of low-lying

residential areas within 10 miles of shore. Storm surge over 18 feet above

normal.

Examples: Only three made landfall in the U.S.: The Labor Day

Hurricane of 1935, Hurricane Camille in 1969, and Hurricane Andrew in 1992

|